The Grand Inga Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo aims to create a 42,000 MW hydroelectric complex upstream of the Inga Falls—double the capacity of the Three Gorges Dam in China and enough to cover one-third of Africa’s electricity demand. Located 225 km southwest of Kinshasa, the site already houses Inga I (351 MW) and Inga II (1,424 MW), which are currently operating at approximately 20% capacity.

The Grand Inga project in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is arguably one of the most ambitious energy projects in the world. Located on the mighty Congo River near Matadi, this mega-dam could eventually become the largest hydroelectric power plant on the planet, with a theoretical capacity of over 40,000 megawatts (MW), the equivalent of several dozen nuclear power plants.

The Inga site is not new: two dams (Inga I and Inga II) were built there in the 1970s. Grand Inga, envisioned at that time, is a titanic extension of the Congo River’s untapped hydraulic potential. It consists of several phases, including Inga III (planned at 11,000 MW), which would serve as the first stage of the entire project.

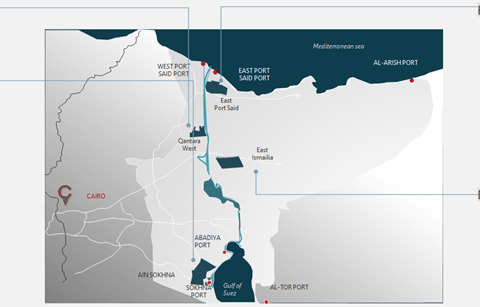

The objectives are multiple: to provide cheap electricity to the DRC, where only 20% of the population currently has access to electricity, to power mining industries, to export electricity to neighboring countries (South Africa, Angola, Nigeria) and, in the longer term, to connect this energy source to North Africa and even to Europe via a high-voltage transmission network.

But carrying out this colossal project faces numerous challenges. The cost is estimated at more than $80 billion for the entire complex. Financing is struggling to materialize, despite interest from several stakeholders, including Chinese, Spanish, and South African consortiums. Political uncertainties, fragile governance, corruption risks, and geopolitical tensions are also hampering the project’s progress.

On the environmental and social front, Grand Inga is a source of debate: the dam could affect unique ecosystems and lead to population displacement. NGOs are calling for rigorous impact studies and transparent governance to ensure that the project truly benefits local populations and not just large companies or export markets.

Yet Grand Inga remains a symbol of hope: that of an Africa harnessing its resources to build its energy future. In a world seeking low-carbon solutions, such a project, if conducted responsibly, could make the Congo River the beating heart of the continent’s energy transition.

- Project stages:

-

- Inga III(4,800 MW), first phase estimated at $14–18 billion, in Sino-Spanish partnership, with 2,500 MW intended for South Africa.

- Subsequent phases (up to 7 dams) to reach 40,000 MW, with the ambition of serving southern, central, West Africa and even Egypt.

- Key issues:

-

- Regional energy integration: a coupling via “electric highways” across Africa.

- Governance and financing: financed in particular by the AfDB, the World Bank (withdrawn in 2016, returned for Inga III) and Chinese, Spanish and Australian consortia.

- Political and social challenges: concerns about corruption, transparency, population displacement and biodiversity protection.

- Expected results:

-

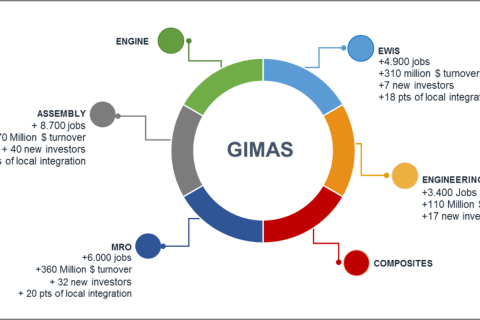

- Electrification of tens of millions of households, industrial development (mines, aluminum smelting, green hydrogen) and export of surplus to neighboring countries.

- Creation of thousands of direct and indirect jobs, boosting infrastructure projects (high voltage lines up to 15,000 km).

- Transition to large-scale renewable energies and strengthening regional energy sovereignty.

- PerspectiveDespite its potential, Grand Inga remains dependent on securing financing, purchasing power agreements with governments and businesses, and clear governance. The launch of Inga III, postponed since 2021, remains the sine qua non condition for initiating the next phases.