CONTEMPORARY MACROECONOMIC CONTEXT OF AFRICA

The most general characteristic of the continent is that its economy and exports are based on extractive industries. About half of sub-Saharan African countries are net exporters of primary products, and unlike elsewhere, exports of extractive products have increased in importance since the 1990s, making the region one of the most commodity-dependent parts of the world, roughly on par with the Middle East and North Africa. This leads to a strong dependence on international commodity prices. For example, 80% of Algeria's exports are petroleum products. In 2014, oil and its derivatives, along with liquid or gaseous natural gas, accounted for 53.3% of the continent's exports.

Africa is rich in oil and minerals, holding 30% of the world's mineral reserves. It is also abundant in available agricultural land, fueling a new rush on Africa, particularly by Gulf countries and emerging economies like India and China, which are buying up land on the continent. About 5% of Africa's surface area is owned or leased for long periods by foreign countries. This phenomenon is referred to as land grabbing.

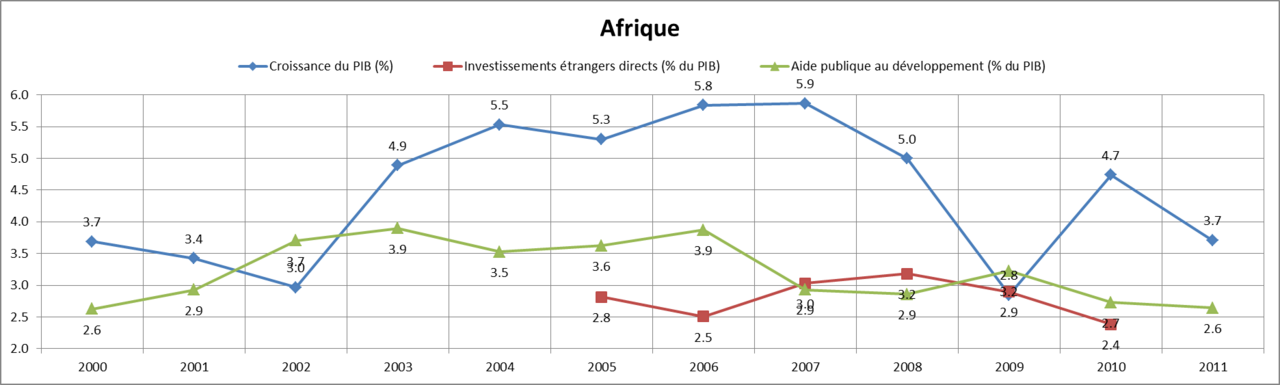

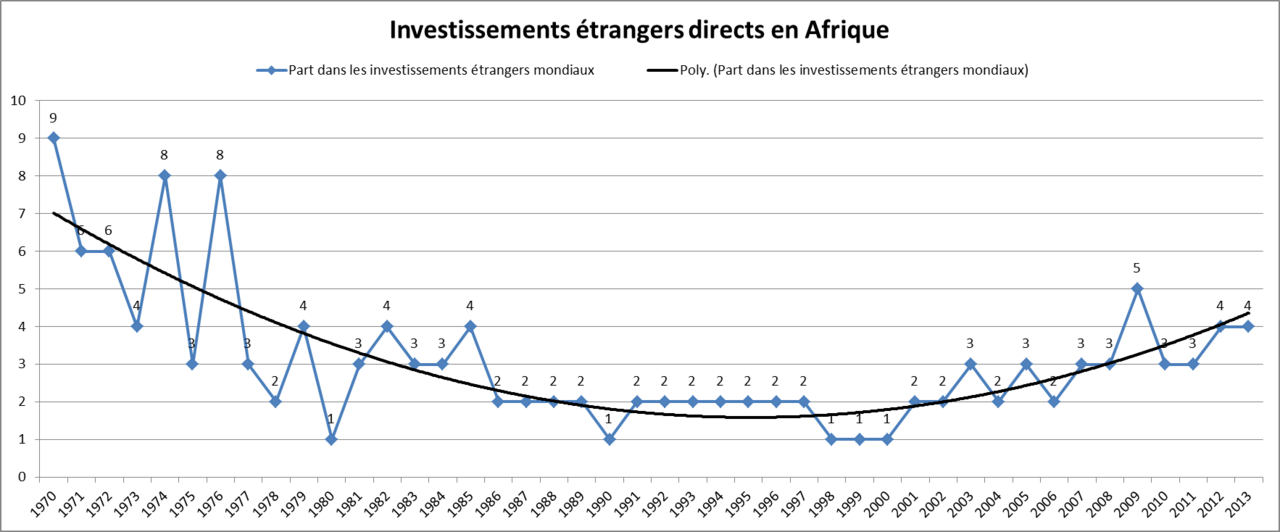

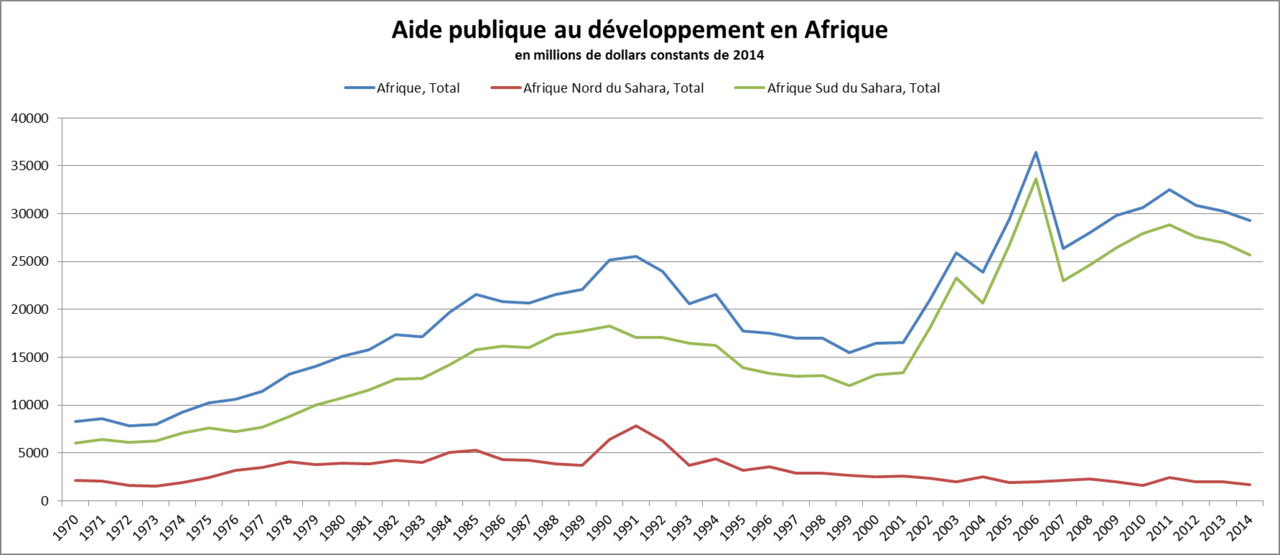

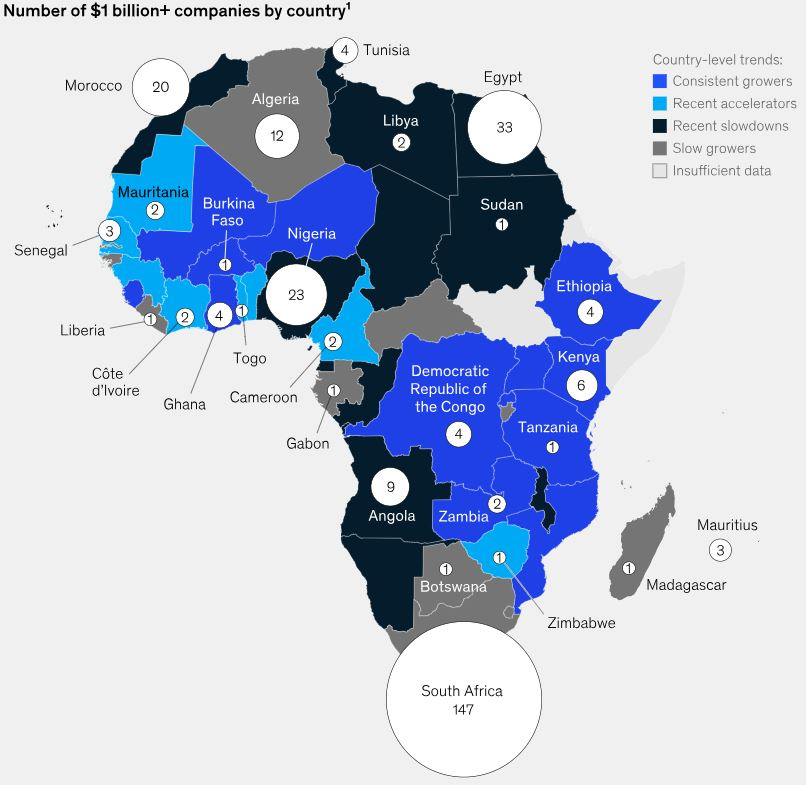

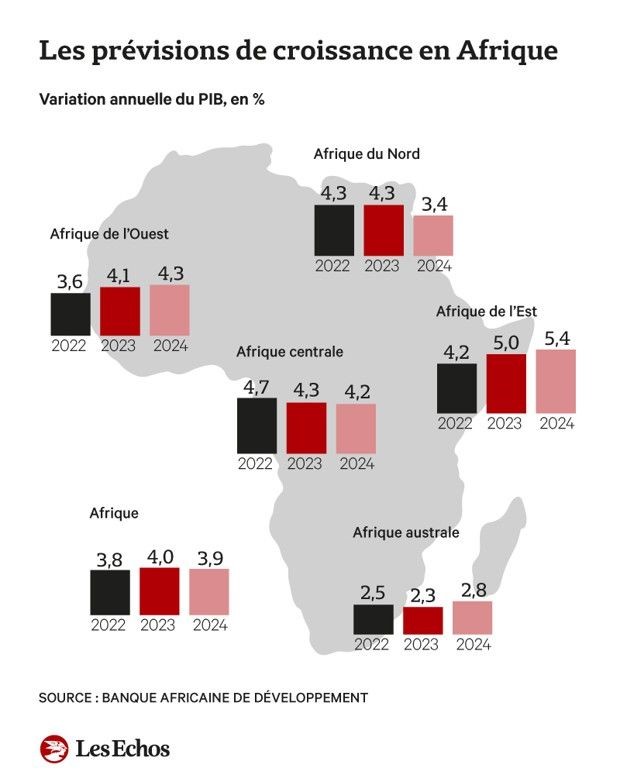

Taking advantage of a bullish supercycle in raw materials, GDP growth in Africa, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, has been continuous and sustained, outpacing the world average since the beginning of the 21st century. "Africa recorded a growth rate of 5.1% between 2000 and 2011, despite the global crisis that caused this rate to fall to 2.5% in 2009. Productivity grew by around 2.7% during the 2000s." However, there are significant disparities between countries and sub-regions. In 2011, GDP per capita in purchasing power parity in North Africa ($7,167) was almost three times that of sub-Saharan Africa ($2,391). Social inequality is also very high. Growth slowed in 2015 due to the fall in commodity prices, which are the continent's main source of income, as was the case in 2009 due to the global crisis. Nevertheless, strong demand from emerging middle classes should sustain growth, and the long-term outlook remains positive.

However, the continent is "behind" (34 of the 48 least developed countries are in Africa) and has poor performance. In 2014, GDP per capita in purchasing power parity was $3,513 for sub-Saharan Africa, while the world average was $14,956. In 2018, the African continent's GDP was estimated at $2,510 billion (USD) by the IMF, representing 2.8% of the world economy.

Consequently, many studies have examined the causes of this phenomenon, which some call the curse of the tropics. Demographic factors (fertility, etc.), political factors (weakness of the rule of law, etc.), historical factors (influence of colonization, etc.), infrastructural factors (insufficient energy production, etc.) have been highlighted, or the curse of borders (states that are too small, landlocked, etc.) has been invoked, or even, noting the weight of extractive industries, the Dutch disease (or curse of raw materials) and the phenomenon of the rentier state that goes with it (capture of rent income by an oligarchy to the detriment of the population).

There are, however, some economic "miracles" that challenge broad generalizations. Botswana, rich in diamonds but landlocked, achieved exceptional economic performance in the 20th and 21st centuries, overcoming the challenges of Dutch disease and being landlocked, while maintaining governance and transparency unmatched by most of the continent. However, Botswana also faces a very high prevalence of AIDS, with a rate of 25.2% among the 15-49 age group. Mauritius, starting from a situation where sugar represented 20% of GDP and more than 60% of export revenues, focused on industrialization in the textile sector, then on services, including tourism. Its growth was 5% per year for 30 years, and its per capita income, which was $400 at the time of independence, is now $6,700 (estimated at $18,900 PPP in 2014). Its education system is efficient, and its ranking in the World Bank's Doing Business ranking (28th) is better than that of France (31st). Rwanda is another miracle. After the 1994 genocide that left it in ruins, the country, firmly taken back in hand since then by Paul Kagame, has managed to develop strongly despite an extremely high population density of 420 inhabitants/km2, more than ten times higher than the average for the continent. By focusing on education and achieving the demographic transition, Rwanda has become a model of redistribution and inclusive growth in Africa, showing that economic backwardness is not inevitable.

The continent therefore has no insurmountable geographical, cultural or structural handicaps, no curse that would overwhelm it; it is the policy that created Rising Africa and which will allow it to prosper in the future.

For the time being, the delay is very real, the very use of the term "miracle" indicating that these are only counter-examples in an Africa that remains the "continent of poverty". Even if poverty is declining, the proportion of poor people living in Africa is nevertheless increasing, showing that this decline is less rapid than elsewhere on the planet. Among the millennium goals, the indicators concerning food insecurity and poverty are those which are progressing the least.

For more information:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portail:Afrique

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa

https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

https://etudes-africaines.cnrs.fr/

https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents-publications/economic-perspectives-en-afrique-2024