AFRICA AND COLONIAL DOMINATION

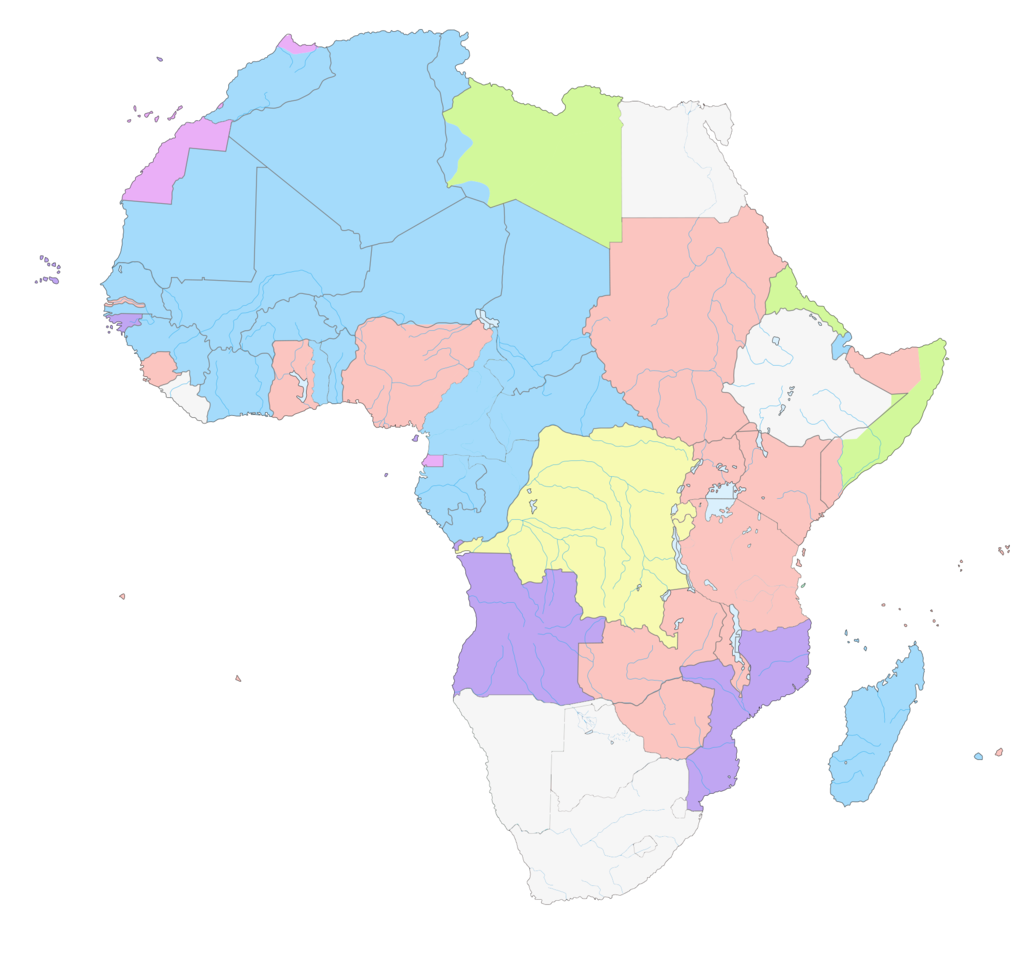

In 1880, less than 20% of the continent was in European hands at the dawn of mass colonization. These were coastal areas in the West, while East Africa was free of European presence. Only southern Africa was significantly occupied, up to 250 km inland, as well as Algeria, which was conquered by the French in 1830. Between 1880 and 1910, due to the technological superiority of the Europeans, almost all of its territory was conquered and occupied by the imperialist powers that established a colonial system. The period after 1910 was essentially one of consolidation of the system.

This rise caused tensions among European countries; this was particularly the case in the Congo region, where Belgian, Portuguese, and French interests clashed, and in southern Africa, where the British and Afrikaners fought. To deal with the situation, the European states organized the Berlin Conference in late 1884 and early 1885, in the absence of any African representatives, which resulted in a treaty setting out the rules to which the signatories agreed to submit as part of their colonization process. This had the effect of accelerating colonization and therefore the deployment of the "3 Cs" (commerce, Christianity, civilization) in the name of the "white man's burden."

Two countries escaped the division of Africa: Liberia, created by an American colonization company in 1822 and having proclaimed its independence on July 26, 1847, and Ethiopia, a sovereign state since Antiquity, which managed to repel the colonization attempt of the Italians, to whom it inflicted a defeat at the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896. This was the first decisive victory of an African country over the colonialists.

What French speakers call "the sharing of Africa," thus emphasizing the consequences for the continent, is called Scramble for Africa by English speakers, who thus highlight the causes. This term is correlated with the economist analysis which suggests that this colonization was triggered by the need for raw materials of the European economies, engaged in the industrial revolution and international trade. The term also refers to the economic competition between nations on African soil. For the economist's meaning, inspired by John Atkinson Hobson, imperialism and colonization are the consequences of economic exploitation practiced by capitalists and the result of rivalries between nations.

Colonial Africa in 1914. Colonial Africa in 1930.

Most colonial regimes put an end, de jure, to slavery in their zone of influence—although the practice continued de facto for a long time to come—thus assuming a role of "civilizing mission." This is a second explanatory part of the "rush": the feeling of superiority of Europe vis-à-vis Africa, reinforced by the theories of Darwinism and social atavism as well as by the period of the slave trade, which had seen the rise of racist sentiment and the idea of hierarchy between races (a school of thought called racialist, embodied for example by Gobineau, author of an Essay on the Inequality of Human Races in 1855), all of this justifying bringing civilization and Christianity to the peoples of the "dark continent," via the "sword and the holy water sprinkler."

Finally, the nationalist sentiment of European countries also plays a role, the competition for domination of Africa being one aspect.

The colonial economy that was established was based mainly on two sectors: mining and the trade of agricultural products. The internationalized commercial activity (trade economy) was in the hands of the Europeans via their import-export firms, which had the capital necessary for local investment.

Several mechanisms structure this economy: the poll tax, which forces Africans to work as wage labor on behalf of the colonists to pay the tax, compulsory plantations, "abject" forced labor and migratory labor, population displacement, land seizure, the native code in its various variants which exclude the colonized from common law, British indirect rule. This significantly disrupts existing social structures and the economic system, which leads to poverty, malnutrition, famines, and epidemics. These practices, already brutal, are aggravated by bloody repressions against uprisings and resistance. The repression of the Hereros (1904-1907) is arguably the first genocide of the 20th century.

The First World War mobilized 1.5 million African combatants, and, in total, 2.5 million people were affected by the war effort.

The period that followed, up to the dawn of the Second World War, is called the "heyday" of colonialism; colonial powers built roads, railways, schools, and clinics. Nevertheless, "the period 1920-1935 remained a harsh colonial period. During the Great Depression [1929], there was deep poverty." Africa became increasingly integrated into the world economy, and the continent benefited from the recovery—interrupted by the Second World War—that followed the crisis of 1929 until about 1950, when corporate profits peaked.

For more information:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portail:Afrique

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa

https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

https://etudes-africaines.cnrs.fr/

https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents-publications/economic-perspectives-en-afrique-2024